Micro-pessimist and macro-optimist, Dyslexic entrepreneurs, Children are scientists

Weekly I/O #125: Micro-Pessimist Macro-Optimist, Dyslexia and Delegation, Children as Scientists, Loving Attention Beats LGTM, Principles not Methods

Hey friends,

This week is about craft and learning. Two inputs are about feedback: how to be strict on details without killing momentum, and why loving attention beats LGTM culture. And two are about developmental psychology from kids to entrepreneurs.

Happy learning!

Help you absorb better with Forward Testing Effects

Input

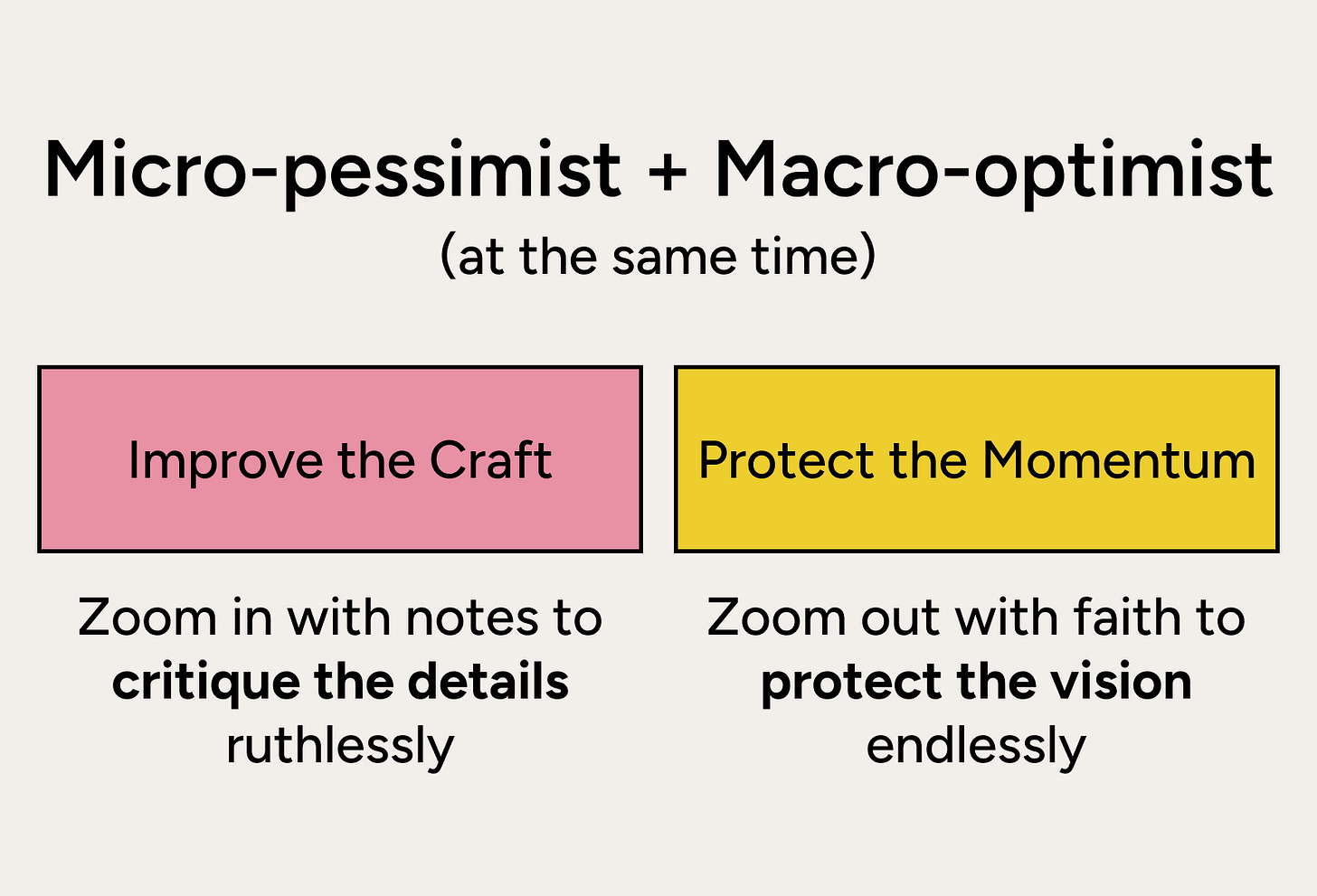

1. Zoom in with notes to improve the craft, zoom out with faith to protect the momentum. Be a micro-pessimist to critique the details ruthlessly and a macro-optimist to protect the vision endlessly.

Podcast: 35: Brie Wolfson - Loving Attention & Ease in Craft

Great feedback holds two opposing perspectives simultaneously.

Brie Wolfson, former Head of Editorial at Stripe Press, describes this as being “a micro-pessimist and a macro-optimist.” When you zoom in, you should ruthlessly critique the details. Nothing escapes scrutiny.

But when you zoom out, you protect the vision. You keep the creator excited about the work. You remind them why this matters.

This balance is hard because most people default to one extreme or the other.

Pure pessimists kill projects before they can breathe. Pure optimists let mediocrity ship. The best feedback needs to do both: scrutinize like a critic, believe like a champion.

I find this framework useful beyond giving feedback. When evaluating my own work, I tend to be either too harsh or too generous, depending on my mood. Zooming in with notes and zooming out with faith gives me a structured way to do both.

And when receiving feedback, I remind myself: we should push for harsher feedback while staying macro-optimistic ourselves.

This also connects to two previous inputs on feedback (three feedback questions, four types of feedback) and the two on holding opposing ideas (scientists and ambiguity, Augustine’s divided will).

2. 35% of entrepreneurs have dyslexia compared to less than 1% of corporate managers. The coping strategies dyslexics develop early, especially delegation and learning from mentors.

Paper: Dyslexic entrepreneurs: the incidence; their coping strategies and their business skills

Why do so many entrepreneurs have dyslexia?

A 2009 study by Julie Logan found a higher incidence of dyslexic traits among entrepreneurs than among corporate managers.

While less than 1% of the corporate managers reported being dyslexic, 35% of the US entrepreneurs identified as having dyslexia. Dyslexic entrepreneurs also reported managing significantly more staff than non-dyslexics.

Julie Logan argues that coping strategies in childhood can become business strengths. Delegation is the big one. If reading and writing are harder, you learn to ask for help early, build a team, and focus on what you do best.

Dyslexic entrepreneurs were also heavily influenced by role models (oftentimes within a family business) and mentors. Conversely, non-dyslexics were more likely to cite education as a primary influence.

I found this paper through Conversation with Tyler where Brendan Foody describes a similar story. Dyslexia forced him to delegate sooner, and it taught him comparative advantage in a very personal way. This does not mean dyslexia causes entrepreneurship, but it does show how constraints can shape useful skills.

3. Children learn more like scientists than adults. Children are “high-temperature” learners who explore wild possibilities with flatter priors, while adults are “low-temperature” learners who exploit known solutions with peaked priors. This makes children better at overturning established beliefs.

Children are oftentimes better scientists than adults.

Alison Gopnik, a psychologist and philosopher studying how children construct theories of the world, argued that children actively construct theories of the world, much as researchers do. They observe patterns, form hypotheses, and update their beliefs when evidence contradicts expectations.

The difference is in what Gopnik calls “priors.” Adults have “peaked priors,” meaning their extensive experience makes them stubborn. They’ve seen a lot, so they require massive evidence to overturn an established belief. When they change views, they do so incrementally.

Children have “flatter priors.” They haven’t accumulated as much experience, so they’re more willing to accept unusual outcomes. They’re not yet anchored to a particular worldview. This makes them better learners in some ways, more open to data that would surprise an expert.

Gopnik uses the concept of “simulated annealing“ to explain this. Children represent a “high-temperature” phase: noisy, bouncy, random. They explore wild possibilities without worrying about efficiency. Adults are in a “low-temperature” phase: making small adjustments to existing knowledge, filling in details.

This is similar to the difficulty of training one’s thoughts lies not so much in developing new ideas but in escaping the old, and reminds me of the quote “You are only as young as the last time you changed your mind”.