Why we sabotage our goals, How ideas stick, Learning sweet spot

Weekly I/O #124: Augustine's Divided Will, SUCCESs Framework for Ideas, Zone of Proximal Development, Seven Sins in Product, Personal is Creative

Hey friends,

This week’s inputs explore why we act against our own goals, how to make ideas memorable, what drives consumer behavior, the source of creative originality, and how learning actually works.

Happy learning!

Help you absorb better with Forward Testing Effects

Input

1. Augustine’s Divided Will: We sabotage our own goals not because we’re weak, but because we genuinely want contradictory things at the same time. The conflict isn’t a flaw to fix. It’s what being human feels like.

Article: Augustine of Hippo (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Why do we skip the gym when we genuinely want to be fit? Why do we procrastinate on work we actually care about?

Augustine of Hippo, a 4th-century philosopher, observed that we simultaneously want contradictory things. He famously prayed, “Lord, make me chaste—but not yet.”

He genuinely wanted spiritual purity while also craving physical pleasure. Both desires were real.

This is the divided will: humans don’t have one unified will. We have multiple conflicting desires pulling us in different directions simultaneously.

We want to exercise and stay comfortable. Be productive and relax. Both are genuinely us.

Most people respond to failure with self-criticism: “I’m lazy. What’s wrong with me?”

Augustine offers a different response. If inner division is universal and not a personal defect, then instead of asking “Why am I so weak?” ask “Which competing desires am I experiencing?”, “What do I want now, and what do I want later?” These questions create space for strategy.

We are not broken. We are just divided.

Acknowledge both desires: “I want to exercise, AND I want comfort.” Then find creative solutions that address both, like reducing friction to build a good habit or adding rest so the comfort side of us isn’t ignored.

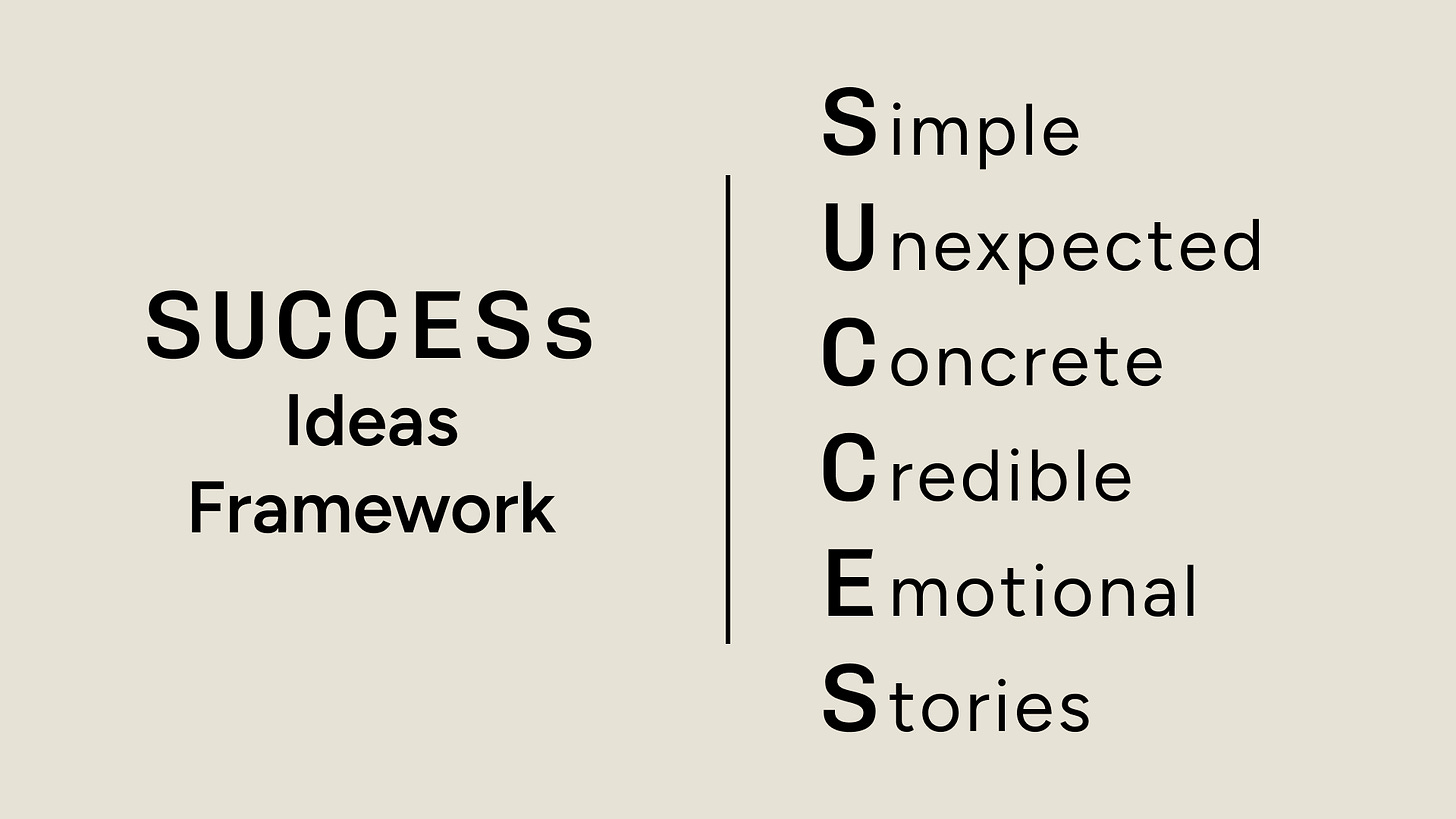

2. The SUCCESs framework: Ideas stick when they’re Simple, Unexpected, Concrete, Credible, Emotional, and wrapped in Stories.

Book: Made to Stick

What makes some ideas survive while others die? Chip and Dan Heath proposed a six-trait framework of ideas that people remember. They call it SUCCESs:

Simple. Say one thing clearly. Find the core, not the summary. Most ideas fail because they try to say everything. Sticky ideas say one thing extremely clearly. The audience needs to remember only one sentence tomorrow.

Unexpected. Break predictions to grab attention. Go beyond shock with surprise plus insight.

Concrete. Abstract ideas vanish. Concrete ones stick. Replace “high performance culture” with “Every meeting ends with one decision, one owner, one deadline.”

Credible. Help people believe without authority. Credibility doesn’t always require experts. Use specific details or let people test it themselves. “Try it for seven days and see.”

Emotional. Make people care before they think. People act when they feel. Logic justifies the action afterward. Tie ideas to identity. Show consequences to real people. “This policy decides whether Maria can afford insulin” is better than “Thousands are affected.”

Stories. They’re mental flight simulators. Stories prepare people to act. Show cause and effect and model action. Instead of listing principles of customer service, tell a story about an employee who bent the rules and what happened next.

The Heath brothers showed that smart ideas fail because they’re poorly packaged, while average ideas win because they’re well structured.

Don’t treat stickiness as a talent problem. Treat it as a design problem.

Related: Four Elements of Storytelling

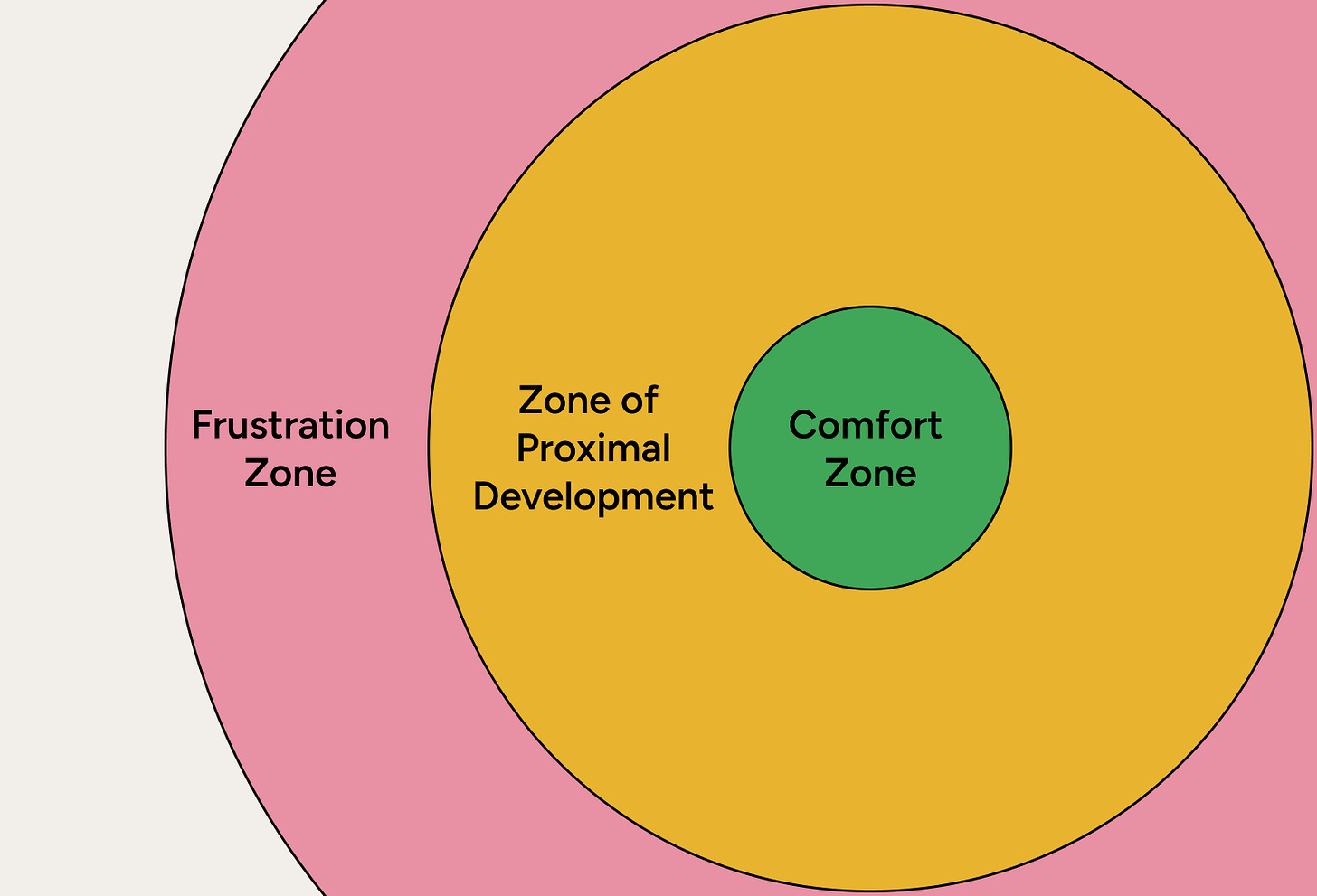

3. The Zone of Proximal Development: Learning happens best in the gap between what you can do alone and what you can achieve with guidance. Too easy breeds boredom. Too hard creates frustration. The sweet spot is in between.

Paper: Generative artificial intelligence: the ‘more knowledgeable other’ in a social constructivist framework of medical education and Zone of Proximal Development

Like the Cognitive Load Theory we noted last week, the Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) is another well-known theory in learning science. Hearing people in edtech mention ZPD always makes me happy because it shows they care about pedagogy.

Lev Vygotsky, a Soviet psychologist, introduced the Zone of Proximal Development to explain how learning actually works.

The core idea: there’s a gap between what a learner can do independently and what they can achieve with help. That gap is where real learning happens.

Think of it as three zones:

The Comfort Zone contains tasks you can handle alone. These demonstrate mastery but don’t promote growth because they’re too easy.

The Zone of Proximal Development is the sweet spot. These are tasks you can’t do alone but can achieve with guidance and support. This is where skills are stretched and internalized.

The Frustration Zone contains tasks that are too difficult even with help. Attempting to teach here leads to discouragement rather than growth.

The ZPD relies on what Vygotsky called the “More Knowledgeable Other” (MKO), someone who can bridge the gap. This is typically a teacher or mentor, but it can also be a peer or even technology (GenAI can be MKO too)

The key mechanism is scaffolding: temporary support structures that help learners accomplish what they couldn’t alone. A teacher might model behaviors, provide hints, break complex tasks into smaller steps, or use visual aids.

As the learner gains competence, the scaffolding is gradually removed, just like physical scaffolding comes down when a building can stand on its own.

Vygotsky also saw learning as fundamentally social. Knowledge begins as something that happens between people and becomes internalized by the individual. The external conversation eventually becomes inner speech, allowing the learner to self-regulate and solve problems independently.