Illusion of Transparency, Hot-Cold Empathy Gap, Worse-Than-Average Effect

Weekly I/O #120: Illusion of Transparency, Hot-Cold Empathy Gap, Worse-Than-Average Effect, Subadditivity Effect, Sins to Fill Void

Hey friends,

This week, we are reviewing and exploring useful psychology concepts and human biases. Happy learning!

Help you absorb better with Forward Testing Effects

Input

1. The Illusion of Transparency: We overestimate how visible our thoughts and emotions are to others. When nervous, we think everyone notices. They usually don’t. This affects how we communicate, lead, and even interact with AI.

Article: The Illusion of Transparency

Whenever you feel nervous during a presentation and think everyone can tell, remember this cognitive bias: illusion of transparency.

We oftentimes overestimate how visible our thoughts and emotions are to others.

Imagine someone pitching an idea. Their minds race with doubt. They’re convinced everyone sees their nervousness. They interpret distracted looks as proof that people have tuned out.

In reality, people see them as confident. At the break, someone compliments their presentation.

This happens everywhere. In relationships, we assume our partner knows how we feel without us saying it. In an organization, leaders assume their intentions are clear to their teams.

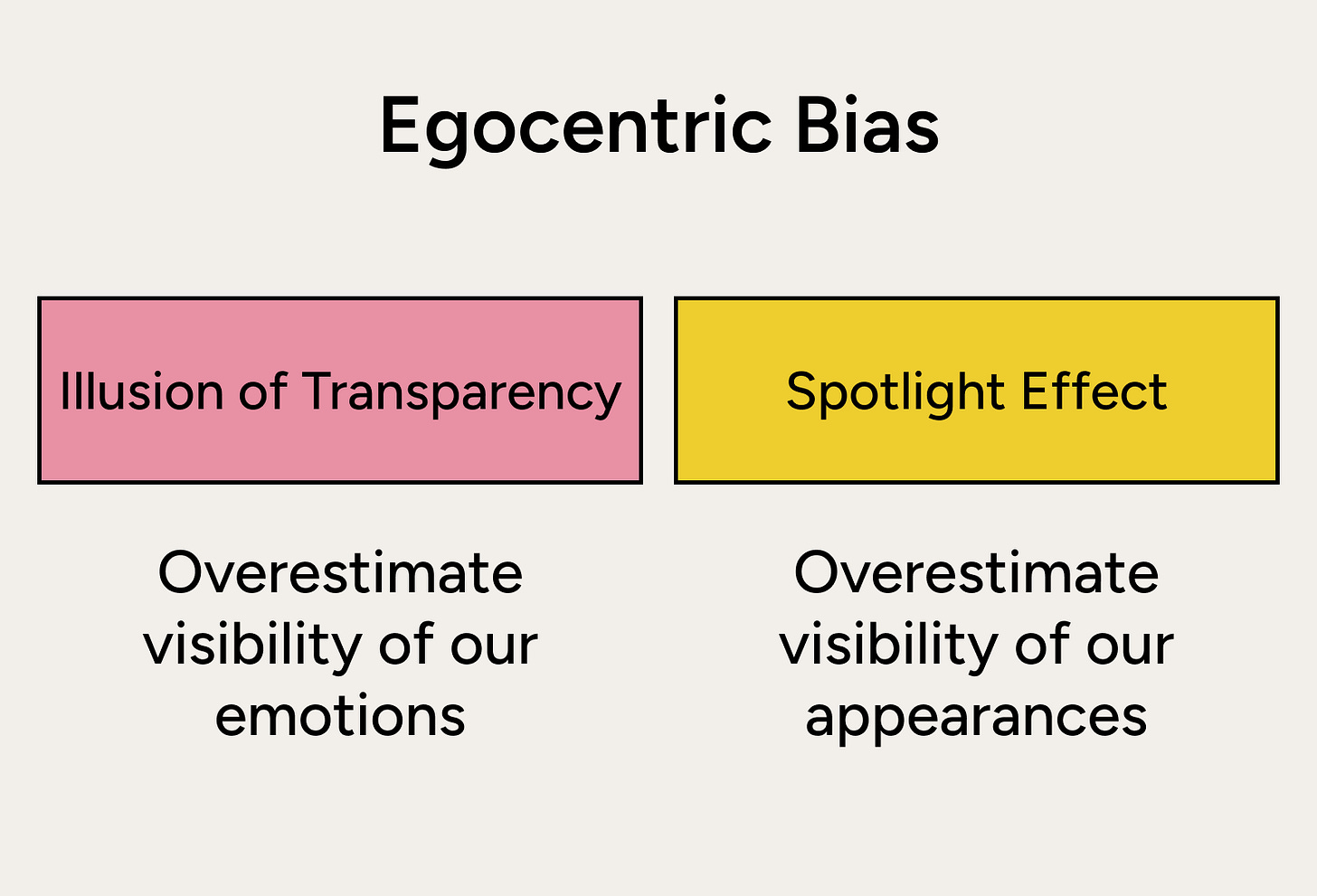

The illusion of transparency relates to the spotlight effect, in which we overestimate how much others notice our appearance. The illusion of transparency is the overestimation of the visibility of internal states.

Both stem from egocentric bias. We naturally anchor to our own perspectives. It’s more efficient to assume others’ perspectives align with ours than to understand what they actually are.

Why does this happen? We spend so much time analyzing our internal states that we struggle to shift focus to others’ perspectives.

This reminds me of three things:

“Nothing in life is as important as you think it is when you are thinking about it.”

When we talk to AI, we get annoyed when it gives an answer that doesn’t match what we meant, even though our prompt was awfully vague. We are expecting it to read our minds.

When we talk to others, we often want to feel understood, even before we fully understand ourselves.

2. The Hot-Cold Empathy Gap: When calm, we overestimate how rational we’ll be when emotional. When emotional, we assume we’ll always feel this way. Both predictions are wrong.

Article: Empathy Gap

Imagine you’re asked how you’d respond if someone unconscious needed help. You’d probably say you’d perform CPR. But if you actually found yourself in that situation, fear and anxiety might cause very different behavior.

This gap is the empathy gap, also known as the hot-cold empathy gap.

“Hot” states are emotional states, such as hunger, fear, and anger. “Cold” states are calm and rational.

The empathy gap describes our tendency to underestimate the influence of varying mental states on behavior and make decisions that only satisfy our current state.

Someone decides to quit drinking. A friend invites them to a party. When deciding to go, they’re confident in their self-control. At the party, anxiety and temptation hit. They didn’t predict this.

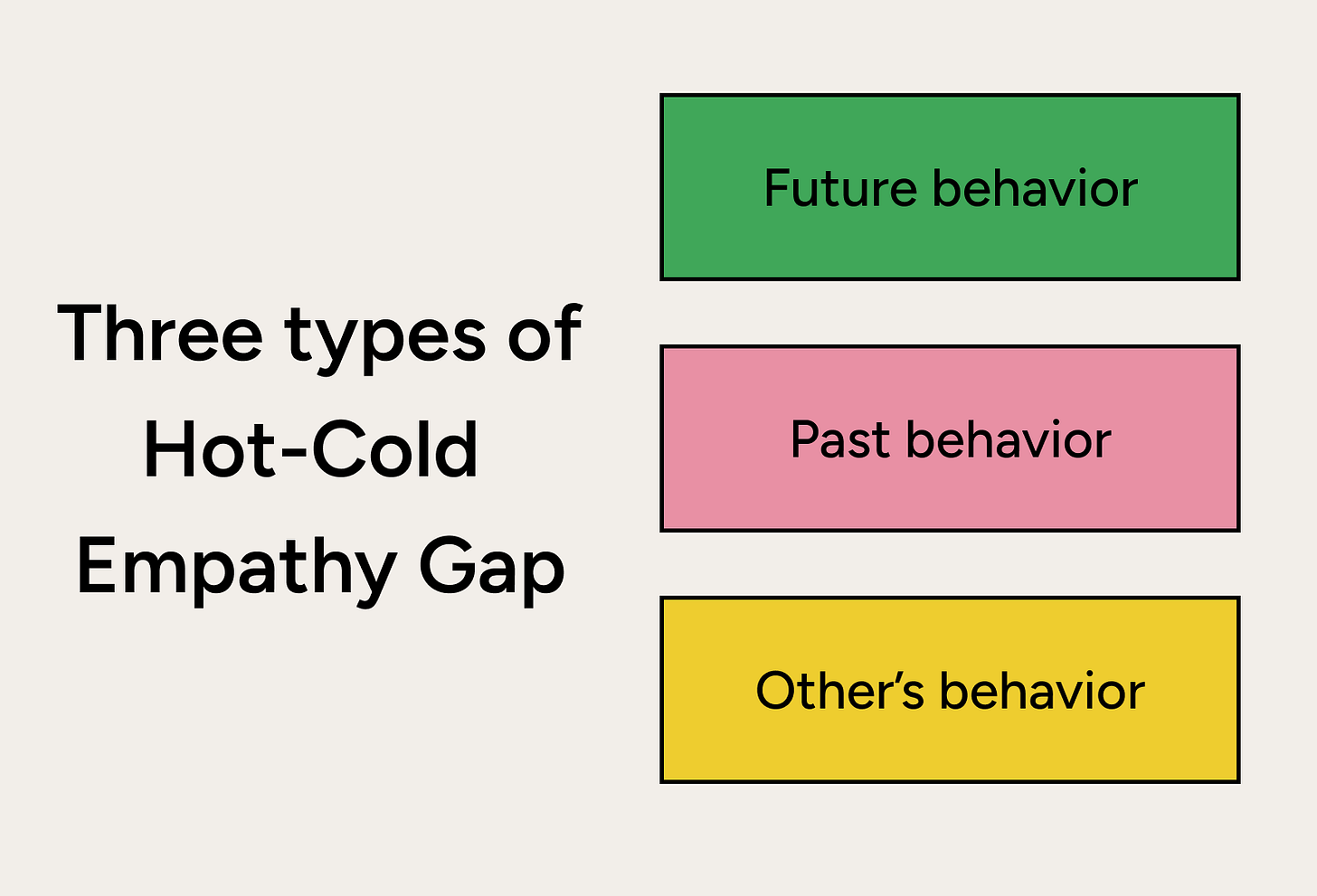

Psychologists identify three types of empathy gaps:

Intrapersonal Prospective (About Future): We can’t predict our future behavior in different emotional states. A smoker who feels relaxed might assume quitting will be easy.

Intrapersonal Retrospective (About Past): We can’t remember why we acted a certain way in the past. After an argument, we can’t comprehend why we lost our temper.

Interpersonal (About Others): We can’t understand others in different emotional states. A well-rested person struggles to understand a sleep-deprived parent’s exhaustion.

Our Weekly I/O’s old friend George Loewenstein tested this in 1999. He asked people how much money it would take to put their hands in ice water. Those experiencing pain right then needed the most money. Those who’d never felt it needed the least.

Our current state anchors our predictions. And the most reliable way to fix it is to use past behavior to predict the future. Visualize different emotional states before deciding.

Before a social event where you’re worried, remember: last time you felt this way, how did it actually go?

3. The Worse-Than-Average Effect: In difficult tasks, we think we’re worse than everyone else. But that difficulty is usually universal, not unique to us.

Article: The Worse-Than-Average Effect

Have you ever felt like everyone else was better at something, even when evidence said otherwise?

That’s the worst-than-average effect. We underestimate our abilities compared to others, especially in areas where we lack confidence. In other words, when a task is difficult, we assume we are worse than average, even if the task might be challenging for everyone.

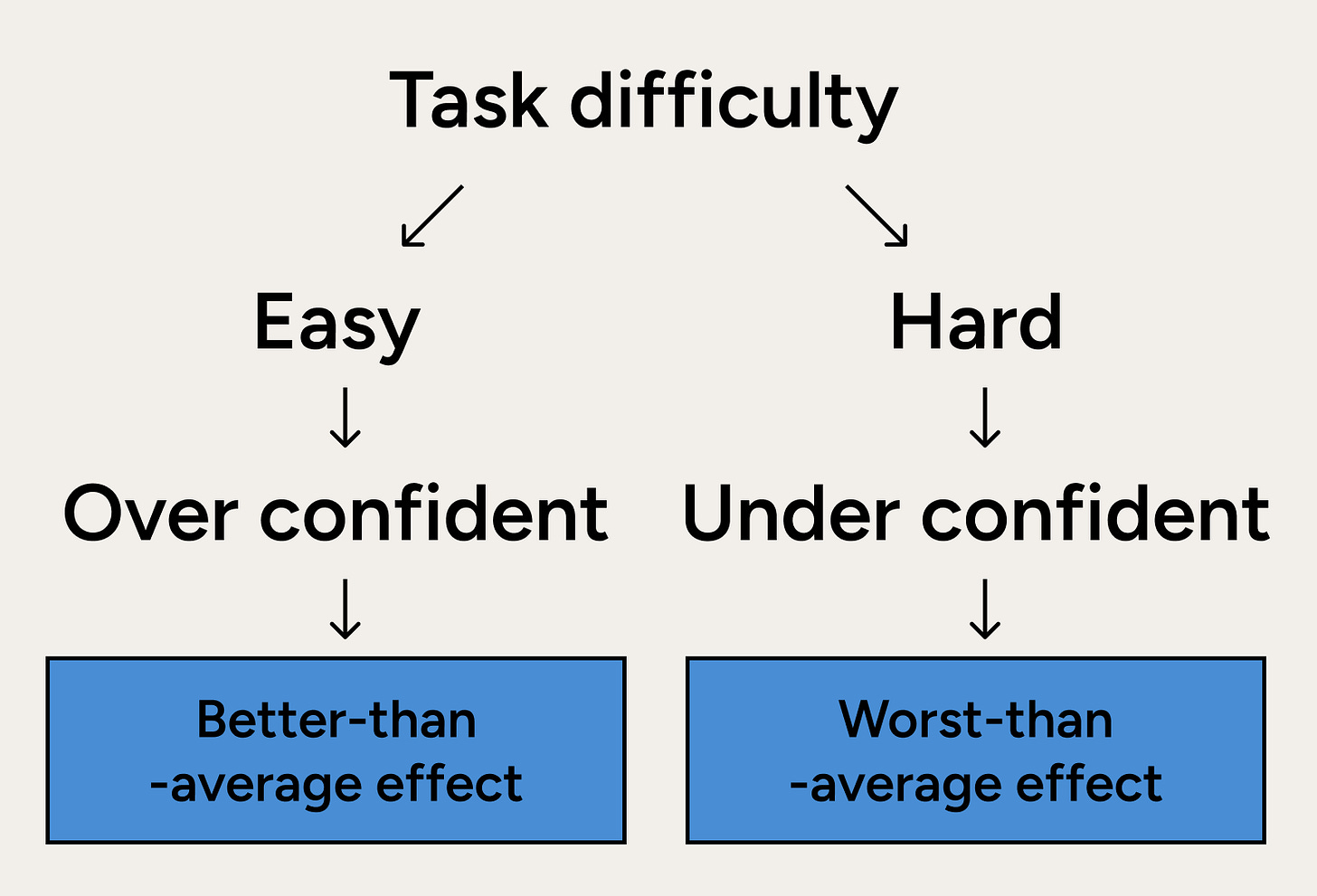

It’s the opposite of the better-than-average effect, where we overestimate our abilities.

Easy tasks make us overconfident. Most people think they’re better-than-average drivers. Challenging tasks make us underestimate ourselves. Learning a new language? We feel behind.

Difficulty acts as an anchor that changes our judgment regardless of low or high self-esteem.

This explains impostor syndrome. High achievers in challenging fields aren’t incompetent. They’re experiencing the worse-than-average effect.