Real Cause of Addiction, MDA Game Framework, What Daoism and Wittgenstein have in common

Weekly I/O #112: Opposite of Addiction is Connection, MDA Game Framework, Daoism meets Wittgenstein, Three Game Loops, Passion Exposed Mediocrity

Hey friends,

Here's your weekly dose of inputs and outputs. Happy learning.

Input

Here's a list of what I learned this week.

1. The opposite of addiction is connection. Addiction isn't about substances or their pleasurable effects. It's a social disorder rooted in the inability to connect with others, which explains why only 10% of people who try addictive substances become addicted.

Article: The Opposite of Addiction is Connection | Psychology Today

Most people believe addiction stems from the pleasurable effects of substances like alcohol, cocaine, or heroin. These substances trigger dopamine releases that make us feel good, so we naturally want more. But there's a problem with this theory: if pleasure alone caused addiction, everyone who tried alcohol would become alcoholic, and everyone prescribed opiates would end up addicted.

In reality, only about 10% of people who try potentially addictive substances become addicted. Why?

Bruce Alexander's Rat Park experiments tried to answer this question. Previous studies put single rats in empty cages with two water bottles: one plain, one with heroin. The rats always chose heroin until they died. Alexander wondered if isolation was the real problem.

He built a paradise for rats, 200 times larger than regular cages, with toys, food, and 20 rats together. Given the same choice, these social rats ignored the heroin. They preferred playing, mating, and interacting with one another. Even previously addicted rats stopped using once they joined the community.

It turns out addiction isn't about substances or their pleasurable effects. It's a social disorder rooted in the inability to connect with others. In other words, the opposite of addiction is connection.

This reminds me of what I learned from Dopamine Nation: connection with others activates our brain's reward system in healthier ways. Authentic relationships restore balance between pleasure and pain rather than tipping us into chronic craving.

An example is Portugal. After decriminalizing drugs in 2001, they focused on helping addicts reconnect through jobs and community. Replacing punishment with reintegration ends up leading to decreases in all drug deaths, adolescent use, and problematic consumption.

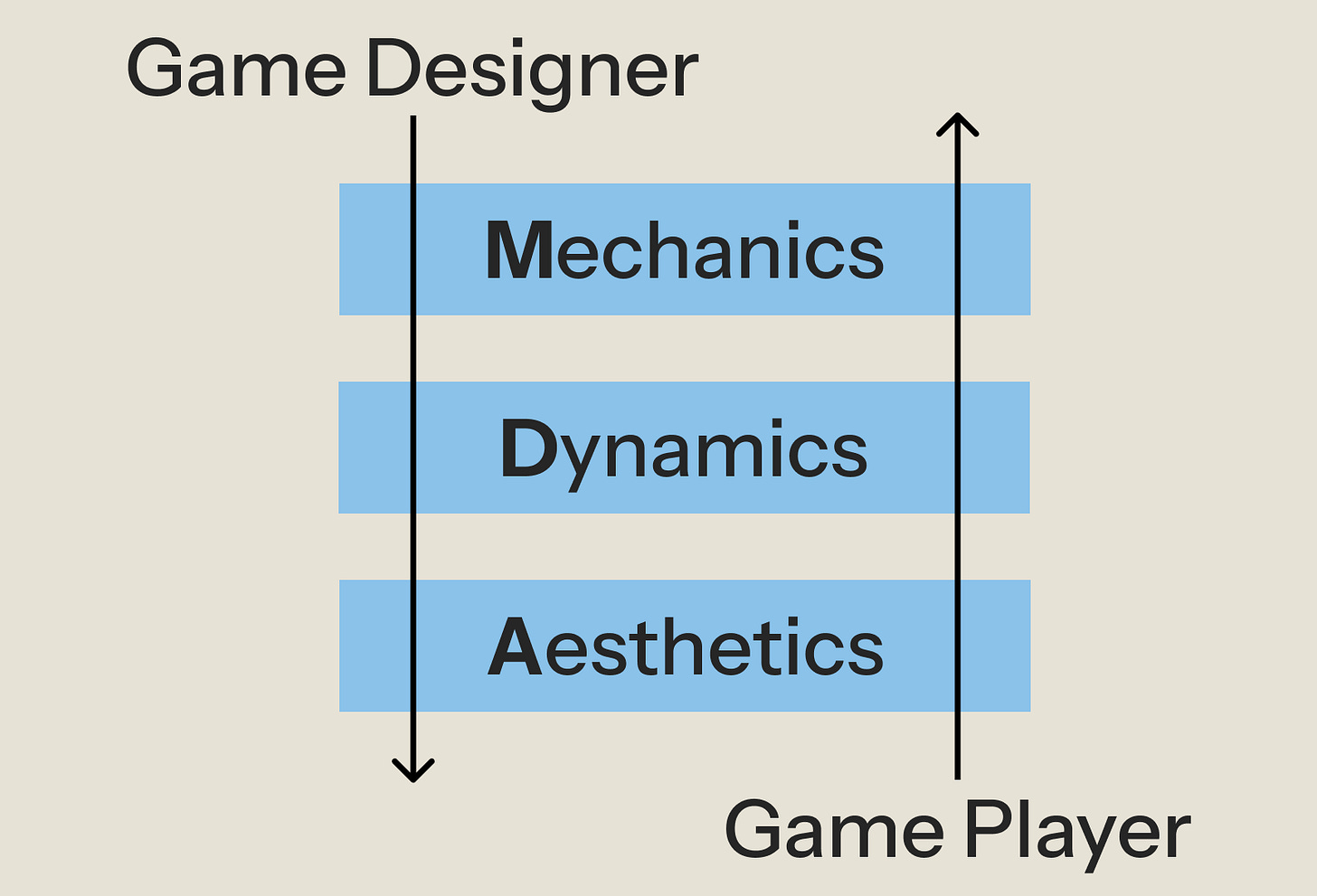

2. The MDA framework breaks games into mechanics, dynamics, and aesthetics, showing how rules create behavior and behavior creates emotion. Designers and players view these components in opposite orders, so designers must work backwards to make the right experience for the players.

Paper: MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research

Why does a game designer's intention not always match the player's experience?

The MDA framework, short for Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics, is a systematic approach to examining games from different perspectives. It formalizes the understanding of games by breaking them into three linked components:

Mechanics describe the particular components of the game at the level of data representation and algorithms. They are the rules, actions, and systems that define what players can do.

Dynamics describe the run-time behavior that emerges from the mechanics acting on player inputs and each other's outputs over time. They are the patterns that arise when players act within the rules.

Aesthetics describe the desirable emotional responses evoked in the player when they interact with the game system. Aesthetics represent the "fun" or emotional responses players feel, including excitement, challenge, fellowship, or discovery.

Take Monopoly as an example. Its mechanics include dice rolls, property buying, and trading. The dynamics involve luck, negotiation, and the accumulation of wealth. The aesthetics range from fun social play to frustration when one player dominates the game.

What makes the MDA framework powerful is that it accounts for both the designer's and the player's perspectives. Designers work forward, building mechanics to generate dynamics and then emotions. Players experience it in reverse. They first feel emotions, notice the dynamics, and only later perceive the underlying rules.

This gap explains why a designer's intention does not always match the player's experience. Therefore, to understand the player's experience, a designer must work backwards. For example, to maintain tension between players (Aesthetics) in Monopoly, the designer should work backwards to shift dynamics by adjusting mechanics, such as taxes or bonuses.

3. Daoism's "Tao that can be spoken of is not the eternal Tao" and Wittgenstein's "Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent" converge on the idea that language cannot capture ultimate truth. If this is true, how far can large language models capture and understand reality?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Weekly I/O to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.