Bomb Under the Table, Why people play games, What makes building beloved

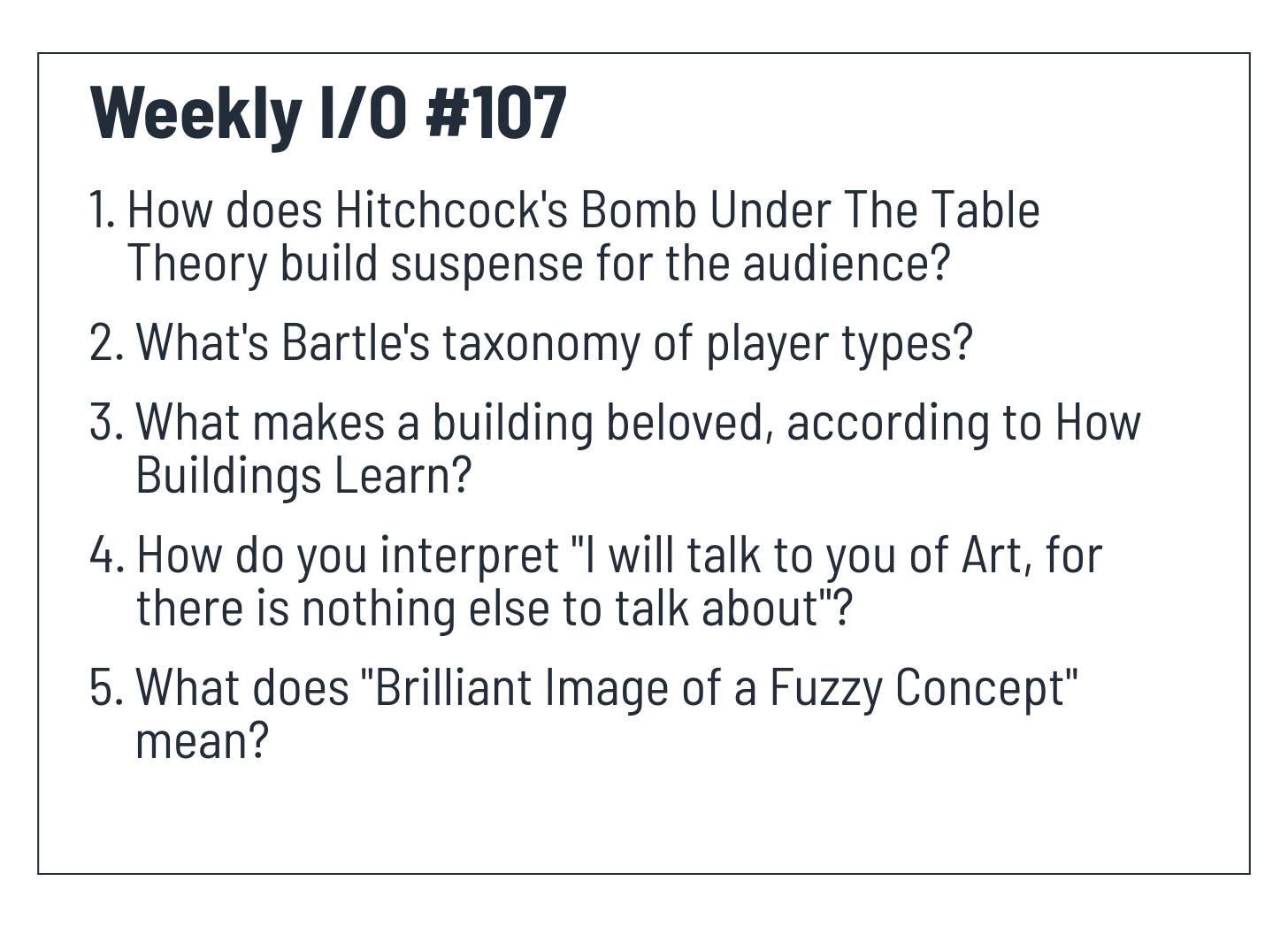

Weekly I/O #107: Bomb Under the Table Theory, Bartle Taxonomy of Player Types, Age and Adaptivity for Building, Omnibus of Art, Perfect Image with Fuzzy Concept

In case you missed the update, Weekly I/O is now available in Chinese! If you're a paid subscriber, you can receive all future Chinese translations directly and for free. Simply reply to this email, and I'll add you to the list.

If you upgrade your subscription now, you can also receive both English and Chinese versions. I hope it's helpful!

Hey friends,

Here's a list of things I enjoyed learning this week:

Malleable software: Restoring user agency in a world of locked-down apps

35 years of product design wisdom from Apple, Disney, Pinterest, and beyond | Bob Baxley

McFly's Movie House: Mastering Film Suspense with Hitchcock’s Bomb Theory

Also experimenting with some new visuals this week, let me know what you think!

Input

Here's a list of what I learned this week.

1. Bomb Under the Table Theory: If you want the audience to care deeply and stay hooked, create 15 minutes of suspense instead of 15 seconds of surprise. Build tensions through dramatic irony and leverage the gap in knowledge between the audience and the character.

Podcast: McFly's Movie House: Mastering Film Suspense with Hitchcock’s Bomb Theory

Two people sit at a table, talking. If a bomb suddenly explodes without warning, the audience is shocked. That's a surprise. Brief and intense.

But if the audience sees someone place the bomb under the table and notices it's set to explode in 15 minutes, while the characters talk unaware. That same conversation becomes nerve-wracking. The clock is ticking. The tension builds. That's suspense.

Alfred Hitchcock, known as the master of suspense, coined this as the "bomb under the table" theory. Giving the audience more information can create more emotional involvement. He called it the difference between "15 seconds of surprise" and "15 minutes of suspense."

Suspense builds through dramatic irony, a literary device that leverages a gap in what the audience knows and what the character doesn't. The audience knows more, waits longer, and feels deeper tension.

Therefore, if you want the audience to care deeply and stay hooked, give them the danger early. Let them WAIT for the boom.

Kuleshov Effect is another cognitive phenomenon used by filmmakers, I learned from Hitchcock in I/O #60.

2. Bartle's taxonomy breaks down game players' motivations by how they engage with game elements (Act/Interact) and where they focus on (World/Players). Game designers should create goals for Achievers, secrets for Explorers, chat tools for Socializers, and competitive arenas for Killers.

Paper: HEARTS, CLUBS, DIAMONDS, SPADES: PLAYERS WHO SUIT MUDS

Ask anyone who plays games why they play, and their response is likely to be to have fun.

But what do people find fun in games?

Game researcher and professor Richard Bartle proposed a taxonomy in his 1996 paper to break down what different players find using two axes:

Act/Interact: How players prefer to engage with game elements? Act means taking direct control and imposing your will on the game or others, while Interact means engaging in two-way participation like connecting, collaborating, exploring, or socializing.

World/Players: Where do players focus their attention? World refers to the game's environment, including rules, lore, systems, and tasks. Players, on the other hand, represent human interaction, such as how you connect with or influence other players.

Therefore, when you combine these two axes, you get four distinct types:

Achievers (Act + World): These players like acting on the world and typically play to win or reach goals.

Explorers (Interact + World): These players enjoy interacting with the world and discovering new things.

Socializers (Interact + Players): These players like interacting with other players and spend a lot of time chatting.

Killers (Act + Players): These players enjoy acting on other players and aim to compete and dominate them through bullying or politicking.

Bartle's taxonomy is useful for game design to balance games and accommodate different player types. For instance, having goals for Achievers, secrets for Explorers, chat tools for Socializers, and competitive arenas for Killers.

According to Interaction Design Foundation, most players are Socializers (~80 %) with Achievers and Explorers each around 10 %, and few are Killers (<1 %). However, this is a simplified distribution because most players blend types. An Explorer may enjoy social chat, while a Socializer may want some achievements.

There are also some updated taxonomies like Yee's, the HEXAD, or the new 3D Player Types Model, but Bartle's four player types remain fundamental.

3. Age plus adaptability is what makes a building come to be loved. The building learns from its occupants, and the occupants learn from it too.

Book: How Buildings Learn

Why do older buildings oftentimes feel comforting and personal despite their imperfection?

Buildings, like living beings, are meant to evolve. A truly cherished building isn't perfect or static. Instead, it tells a story of continuous adaptation and growth alongside its residents.

Age adds charm. Whether it's worn bricks, polished steps, or faded paint, signs of time make us curious about a building's past. Such structures have outlasted transient fashions and become more timeless and relatable.

Adaptation is the other key ingredient. People constantly adjust buildings to fit their lives. They add rooms, modernize kitchens, or convert old factories into trendy apartments. These changes reflect practical needs and creative expression.

Age and adaptation deepen the bond between building and occupant.

MIT's Building 20 is a famous example. Shabby yet beloved. Its imperfections allowed occupants to adapt spaces in unconventional ways. Such buildings teach people how to live and work differently, shaping their habits, routines, and identities. Occupants, in turn, continually shape the building through small modifications.

Ultimately, this reciprocal relationship between a building and its occupants creates a lasting emotional connection. It's why adaptable, aging buildings often feel more like home than perfect, static ones, and architectural design should create adaptable spaces rather than attempting to predict and design for future needs perfectly.

This also reminds me of how languages evolve when there are more people learn it as a second language and evolutionary success with individual suffering.